The EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) was meant to be a done deal, yet support for it collapsed in spectacular fashion last week, with the Directive failing to secure final approval in the European Council. Undoubtedly a setback for anyone who believes that big business should be held accountable for their activities’ impacts on people and planet, my sense is it can only be temporary, for multiple reasons I shall explain. But before I do, a wee bit of background…

What exactly is the CSDDD?

In short, it’s a major piece of EU regulation that would require big businesses based in the EU (or with significant revenues generated there) to conduct rigorous assessment of actual and potential environmental and human rights impacts across their operations, subsidiaries and value chains. Under proposed rules, they would have had a duty to prevent or mitigate any potential impacts identified, and to take steps to minimise or end any actual impacts. Additionally, the CSDDD would have been the first piece of EU law to mandate companies’ development of Paris Agreement-aligned transition plans.

So, why was it scuppered?

Guess what? It would appear that a lot of vested interests don’t want to be held accountable in this way. While many businesses have come out in support for the CSDDD (for reasons described below), other business groups have denounced it as too financially and administratively burdensome – a view echoed by the German Free Democratic Party (FDP), whose machinations have been widely reported as setting in train the domino effect that brought down the deal.

So, why should the setback only be temporary?

1. Because the necessity of robust due diligence processes is already firmly established

The corporate duty to identify, assess, and take action to mitigate or prevent adverse impacts is already core to globally recognised voluntary standards, such as the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. Furthermore, supply chain due diligence and/or disclosure obligations are increasingly core to various national regulatory regimes around the world, as well as existing EU directives, such as on conflict minerals and deforestation-free products.

Ironically (given their de facto ‘nays’ to CSDDD), those national regulatory regimes include France’s Duty of Vigilance Law and Germany’s Supply Chain Due Diligence Act, as well as existing or proposed laws in Belgium, Norway and Holland.

In this context, the argument that the CSDDD represents an unnecessary burden on EU businesses seems odd, if not utterly ludicrous. As many have been keen to point out, including supportive businesses, it provides a much-needed means to harmonise fragmented approaches, and to provide clarity and certainty as to what businesses are required to do (and what liabilities they face if they don’t).

2. Because due diligence is inextricable from double materiality reporting

Double materiality reporting requires that companies assess and disclose not just how sustainability issues impact their business (financial materiality), but also how their activities impact society and the environment (impact materiality). Already core to mandatory disclosure requirements under the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) – which has already passed and takes practical effect from next year – a double materiality approach is also central to new sustainability disclosure guidelines published in China last month, which stands to establish it as the de facto global norm.

The addition of impact materiality assessment necessarily expands the boundaries of reporting to encompass the entire value chain, since that is where most outbound risks and impacts typically reside. Required disclosures include how material issues arise from – and may require adaptation of – business models and value chains, increasing the need for businesses to expressly consider sustainability-related risks, opportunities, dependencies and impacts in the development of corporate strategy.

Surely it’s impossible to make credible disclosures, absent effective due diligence processes to identify actual and potential impacts, and the requisite structures and processes for integrating findings into strategy and the development of appropriate transition plans? The notion that nixing CSDDD nixes these requirements seems suspect to say the least.

3. Because why wouldn’t business leaders want to understand and address their impacts?

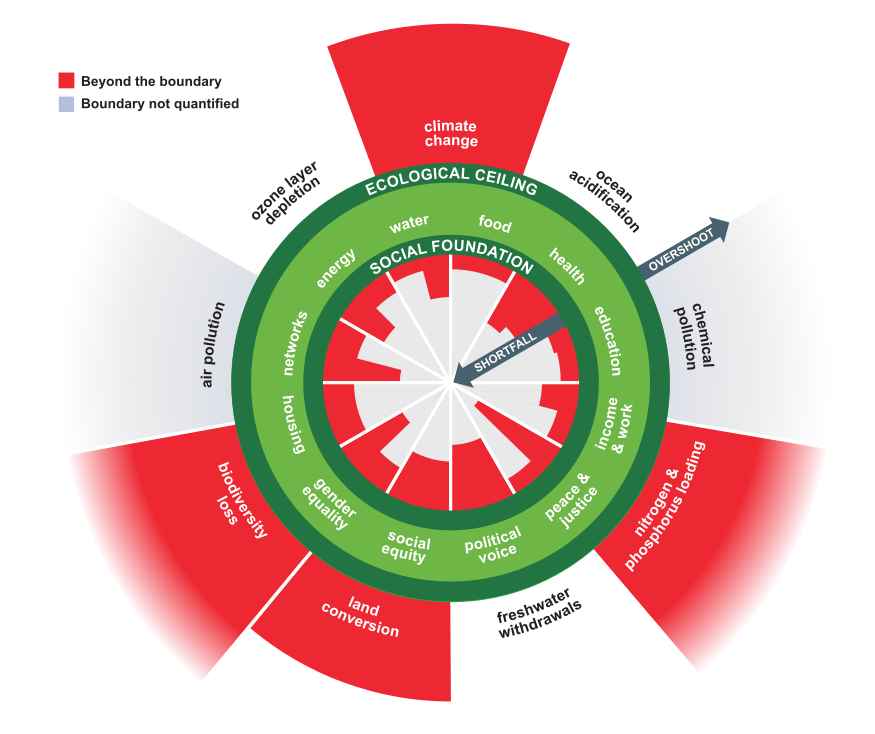

Ultimately, it boils down to this. At the crossroads of impact and financial materiality (and, ideally, with consideration of context-based materiality), we find answers to some pretty fundamental questions, i.e.:

- Impact materiality: How do our activities (and the activities of our suppliers) impact the people, resources and ecosystem services that our business model relies upon to function?

- Financial materiality: How does the quality and availability of those resources and services impact our ability to create and sustain enterprise value?

- In combination (and ideally with regard to the wider context of planetary and social thresholds): How do our dependencies and impacts on those resource and services impact their quality and availability? How does this affect not only the resilience of our business model, but also the health and resilience of the social and environmental systems it’s part of?

In other words, due diligence is fundamental to understanding business model resilience in an era of rapidly changing frame conditions, and the rapidly rising physical, transition and litigation risks that go with them. When ensuring the ongoing viability and success of the enterprise is supposed to be company boards’ primary concern, it’s surely an act of wilful ignorance to deny the necessity of understanding and addressing dependencies and impacts.